Chapter 7: Commissioned service, 1936-1939

It was a pleasure for me to return to the Catterick Camp that I knew. It was a big military station with plenty going on. Our group of seven new Young Officers was made thoroughly welcome from the start. We were reunited with those six months and a year senior to us, friends from our time at Woolwich.

The Signal Training Centre was composed of the School of Signals a Depot and a Training Battalion. We were allotted to one or the other of the latter units for Games, Orderly Officer and parades, in that order of interest for us. Our posting was to the School. Adjusting ourselves to the circumstances was easy. We were new members of the Signals family and were accepted as such at all levels. The Officers’ Mess was a fine building but there were no rooms there for us. Our rooms were a bicycle ride away in a wooden hut of 1916 vintage. Needless to say we were often cold in spite of the smoky coal stoves provided.

What we were going to learn? The first requirement was to acquire the skills needed to qualify for the All Arms Signals course that we would attend. The main job of the course was to train somewhat older officers who were due to become Regimental Signal Officers in their own branch of the Army. Potential Regimental Signal Sergeants had a similar course. There were specified reading speeds to be met in the use of morse code, invented in 1843 and semaphore with flags, a relatively modern innovation and only forty years old. Similar reading speeds were set for signalling by lamp and heliograph. Flag wagging, as it was termed, for ingraining the morse code was great for developing the shoulder muscles and equally great for punishment if the instructor thought we were idle, when he kept us at it for too long without rest.

It was not long before we learned that we were still expected to live in the age of horse and hound. At interviews with the Brigadier Commandant we were individually asked what private means we had. Replies elicited standard responses from him, ‘You can afford to hunt’ or ‘You can help with the beagles’. One bold newcomer, commissioned from the ranks, is reputed to have replied that his private means, probably zero, were ‘private’, but the routine never altered. Those who chose to hunt would be excused lectures for the day. The horse was more important than the ampere. My income was five pounds a week of which a third came from my parents. With no interest in hunting I reserved what I could for other interests.

The All Arms Courses which continued at regular intervals during the eighteen months we were there were of great value to us. Through the contacts made we came to know many young officers, cavalry, infantry, gunner and Royal Marines with the result that wherever we served we were likely to discover some friendly faces in the units of the Brigades we were in. For them selection for Regimental Signal officer was often a step to Adjutant. Peter Hunt, who was on our course, I next met with the Cameron Highlanders in 13 Brigade. I remember him taking me into the large hutted office of Lt Colonel Wimberley, the future Commander of the Highland Division. I stood in one corner whilst the CO took the one opposite me. During the interview this tall figure went through a process of stalking slowly towards me and retreating again only to repeat the exercise. It had a most mesmerising effect. Thirty-five years later Peter Hunt was General Officer Commanding the British Army of the Rhine when I was his Chief Signal Officer. He went on to become Chief of the General Staff.

Perhaps these early experiences were the forerunners of others, which impressed on me the lesson that it is people who are important and that the development of friendships and mutual trust was a key element in military success.

Much of the eighteen months training for newcomers to Royal Signals was directed towards education in what is now called electronics and qualification as Associate Members of the Institute of Electrical Engineers. Nevertheless we spent time on equitation, sword drill and workshop experience. We were kept busy. We worked a six-day week and even our Sundays, with Church parades, were not free. Sunday Church Parade, uniformed for all, took up the full morning. Half days on Wednesday and Saturday were taken up with sport. On five nights a week we donned Mess Kit for a formal dinner, on Saturdays a Dinner Jacket was acceptable and Sundays only required a suit. Guest nights were a regular Tuesday feature. The routine followed was dinner, band performance, roughhouse activities in the Anteroom and no leaving before the last guest departed. The forced jollity was, in my view, an uncivilised practice and did not deserve the classification of entertainment.

An occasional short weekend leave from lunch time Saturday could be fitted in when there was no games commitment and here my family Mafia of relations helped provide hostesses, whilst the county families of Yorkshire were very hospitable.

Two practical elements of our training stand out. There was line laying and the building of overhead telegraph routes. The cable wagon, pulled by a team of horses, was in use for laying field cable. The manning required was seven linemen, which exactly fitted our course. One member had to sit on a seat the size of a soup plate and pull the cable off a heavy drum at the speed required.

.

At the canter across the open moors this could be exciting and even dangerous. One member of the course before ours got a loop of cable round some fingers when at speed and was whipped off his seat, luckily without lasting damage. There would be stops. Numbers one and two would leap from the wagon when an overhead crossing was required, say at a roadside gate. With sledgehammer and jumper (a heavy three-foot long steel spike) holes were made; poles inserted with cable attached and guy ropes fixed. Then it was back on the wagon and away. Number seven followed behind, jumping from his horse periodically to make a tie back or safety improvement and at the same time making sure that his horse did not have ideas of its own about trotting off home whilst the rider’s attention was otherwise engaged. The cable laid was a single core – the ‘return’ circuit being made through the earth – and up to 5 miles in length. After testing, the cable would then be recovered.

Richard Moberly was our instructor and I remember him saying when he had become Signal Officer-in-Chief that he looked upon the cable wagon as the best instrument there was at the time for testing what came to be known a ‘officer qualities’. Later generations are reminded of this earlier equipment and its horses by beautiful sculptural representations on Mess tables of active cable wagon teams.

By the time we reached our active units a few months later, the horse-drawn cable wagon had been replaced by motorised transport. As far as Signals was concerned the horse had been abolished.

A further element of experience related to half a dozen or so mornings learning to ride army motor cycles.

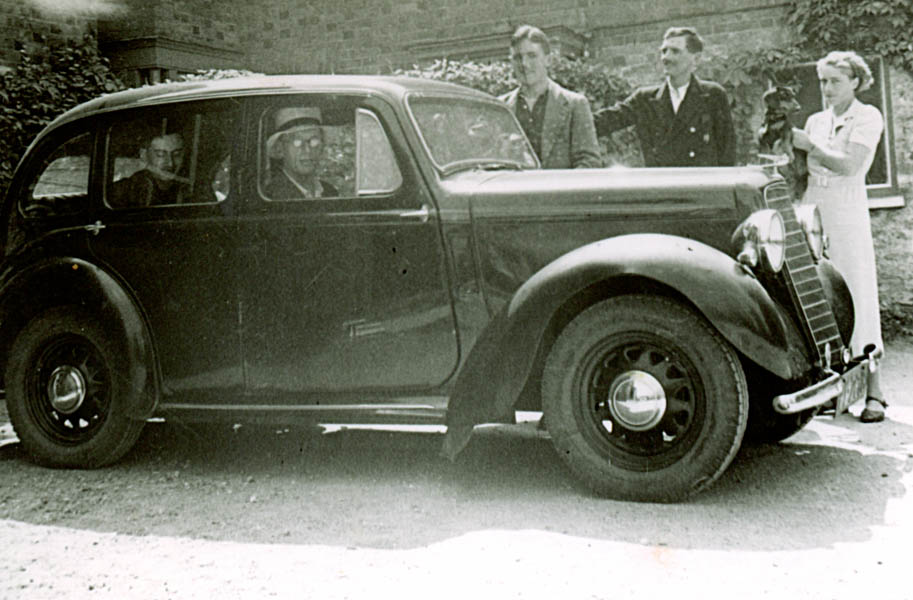

As far as training was concerned another extremely important result was achieved by private enterprise. The motor car was no longer a rarity, but ownership was not widespread by modern standards. Each one of our group soon had a car of his own. A few had new models provided by indulgent parents, but in the main we had to become expert mechanics to keep our machine in working order. The skill acquired was much used by me in keeping my army transport mobile in the early days of WWII.

I was given an aged Morris Cowley two seater that cost £6. It was supposed to be handed over by a salesman outside Lords in London at the time of the Eton and Harrow cricket match that I was attending with my parents. There was some delay in the arrival of my car with the result that I had to set off in the family Alvis for a social engagement of my own, whilst my father, with morning coat and top hat, had to make do with the ‘banger’. By nursing such well-worn relics we all learned a great deal about the vehicles of the age.

Leave was generous at sixty-one days a year. Two quotes might be added from different sources ‘Leave is a privilege and not a right’ or, in frivolous vein ‘An officer is on leave unless actually required for duty’. There was also an underlying suggestion that leave should be spent in adventurous pursuits which would develop ‘character’ and the ability to deal with difficult situations. This direction suited me admirably. Good results could only be achieved financially by the most stringent restriction of spending at other times. For long periods I would deny myself all extras to mess bills. As others have found, such spending discipline becomes a habit that you have to live with. Private enterprise adventure training had high priority. Twenty years later adventure training became a recognised way of developing valuable qualities for all ranks.

I was encouraged to ensure that Nigel’s disability did not mean that he should be left out of exciting enterprises which others were involved in. Our honorary godfather (the Hon) came to the rescue on summer leaves. He invited me and Nigel to join him on expeditions. He would provide the car, whilst we would only pay for our accommodation.

The first tour took us south through France with no firm itinerary. In Bordeaux we endured a French record temperature of 40°C and got some relief in the cellars of the Chateau La Tour vineyard in this famous Claret area.

We moved on to the small Mediterranean port of Sète, supposedly the centre for the production of Sherry from gooseberries. This was the time of the Spanish Civil War and we noted a small steamer holed by shellfire awaiting repair. Choosing a suitable hotel we found ourselves surrounded by spoken English at a time when travellers of our kind were rare. It turned out that we had arrived at the same time as a touring company of the Ballet Rambert, led by the future Dame Marie herself. They were delightful company and we attended their performances during the few days that they stayed. We met them in the hotel and on the beaches, where they had strict instructions not to get too sunburnt.

They had a young man with them as Manager who set off to swim the considerable distance to the lighthouse at the entrance to the harbour. Dame M became more and more agitated, particularly when she saw that there was a flow of ships in and out of the harbour between the swimmer and his target. The Hon and I volunteered to effect a ‘rescue’. We found a boat and rowed until we reached the swimmer. He was not distressed, but our arrival was not unwelcome and we carried him back to our beach. Maude Lloyd, Prudence Heyman and Elizabeth Schooling were amongst several who were to make considerable names in the ballet world.

After their final show they set off by coach after a farewell drink which we provided. We felt it was time to leave too, intending to sleep in the open at any suitable place we found. We had not appreciated that we were running east parallel with a continuous array of étangs, extensive marshy lakes. We had hardly settled down before there was an increasing high-pitched note as millions of hungry mosquitoes homed in on promising prey. We had to move.

On our return through the Gorges du Tarn we must have passed close to Anduze, a Huguenot centre, where my Cazenove grandmother’s family came from via Geneva 300 years ago, but I knew nothing of this family history at the time.

One way in which I could make ends meet was that I had become a ski instructor. I received no pay but by helping a club I was able to get free accommodation. Donald Greenland of the Dôle Ski Club had moved to Andermatt and formed the White Hare Ski Club with the idea that, with this name, he was not tied to a particular resort. It is still there.

In the spring of 1937 my brother Malcolm and I were invited to join my New Zealand friend Harold Taylor and his wife Joan for three weeks of ski mountaineering, unguided but with a ski porter and a gifted Swiss ski instructor friend from St Cergue. Our nights were spent in mountain huts with beds or bunks, wood for a fire and cooking but no staff or provisions. On the worst occasion in a hut called the Cadlimo on the Italian side of the St Gotthard Pass, it never got warm enough to melt the frost on some of the internal fittings. We climbed something over 30,000 feet and became so fit that on one occasion, after a major day’s climbing, Harold and I took in an extra 3000ft for a little more skiing.

We climbed the Blindenhorn in Italy which Mussolini is reputed to have ascended and in another direction from the Albertheim Hutte up the Tiefen Glacier to the Galenstock and then down the length of the Rhône Glacier. For safety we set out in the dark, lit by a smoking candle in a folding tin candleholder. With provisions, a rope and other necessities the weight of a torch with batteries was an avoidable addition to our loads.

Above all the importance of the trip was what Malcolm and I learned from our thirty-year-old leader from New Zealand. We needed expert navigation, knowledge of weather, snow conditions, avalanche danger, mountain safety amongst others - who better than a Cambridge Wrangler to teach us. Safety was our business, not that of a tour operator, a local guide or rescue service.